Special consideration for treatment of systolic hypertension in geriatric population.

Isolated systolic hypertension, a condition in which reading of systolic pressure greater than 140 mm Hg with normal diastolic pressure is a common disorder in old age due to increased aortic resistance. It is a silent killer if left untreated due to the resulting ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, heart failure and kidney failure. Hypertension in general has been implicated as risk factors for coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, aneurysm and dementia. Physicians therefore, are diligent in treating hypertension in their patients with the gold standard of keeping systolic pressure below 140 mm Hg and diastolic pressure below 90 mm Hg if at all possible based on evidence demonstrated in the SHEP study (a major study of systolic hypertension in the 1980s-1990s) as well as other studies of blood pressure in diabetic patients which demonstrated lower morbidity and better outcome with treatment modalities.

However, in patients over 75 years of age (the old-old 75-85, the very old > 85 by gerontology criteria) the issue seems to be more complicated because:

1- In early 20th Century, when physician first learned to use the sphygmomanometer to measure arterial blood pressure, Osler had noticed of a condition in octogenarian he called “pseudo-hypertension” because patients clinically did worse when he attempted to lower their blood pressure.

2- In late 1980s, Luchi and associates while working on patients with vascular dementia reported a narrow window of systolic blood pressure (between 130 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg) for optimized brain performance correlated with cerebral blood flow (using Xenon wash-out technique). Constant systolic pressure readings lower than 130 or higher than 150 were associated with faster deterioration of vascular dementia.

3- Anti-hypertensive have been identified as the second most common cause of drug induced falls with injury in geriatric patients (below the benzodiazepines).

Fortunately, results of the INVEST study released in 2010 appear to clarify this confusion about treatment of systolic hypertension in geriatric patients. Coordinated from University of Florida, this study enrolled 22,576 patients with history of coronary artery disease for treatment of their hypertension and measured their outcomes (all causes of death, non fatal strokes and non fatal heart attacks). In one analysis, patients are grouped by age in 10 year increments (> 80, 70-80, 60-70, <60); there are plenty of patients in each group for statistical purpose.

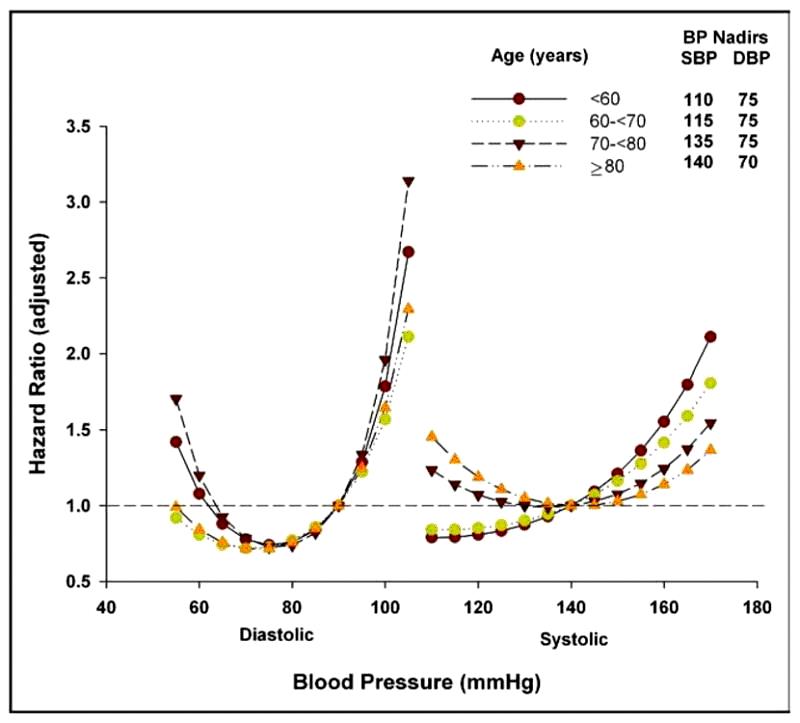

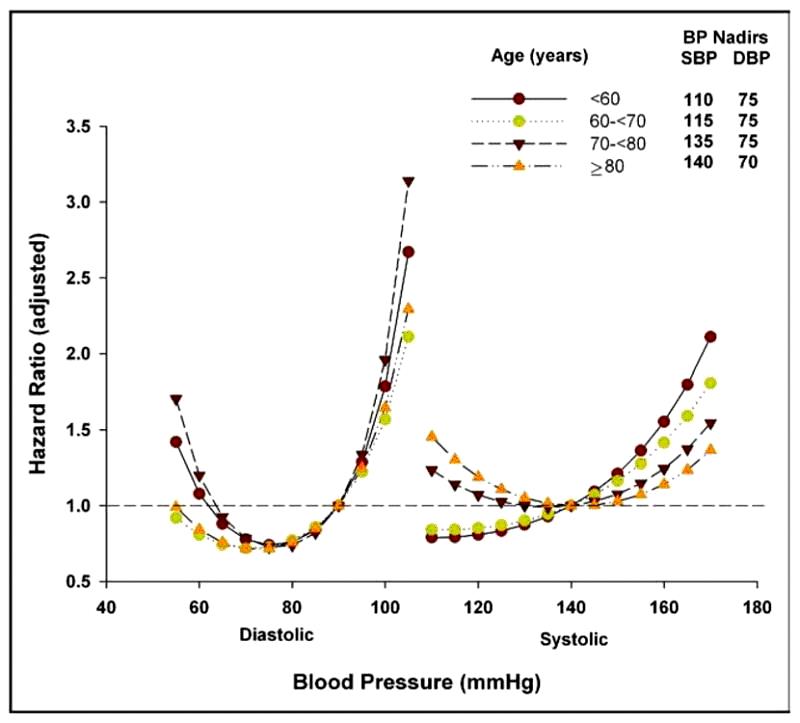

The results are interesting as shown in fig.1:

Notice the J curves of outcomes related to systolic blood pressure treatment (hazard ratio) on patients of 70 and older age groups.

Fig.1: Adjusted hazard ratio as a function of age (in 10-year increments), systolic and diastolic

blood pressure. Reference systolic and diastolic blood pressure for hazard ratio: 140 and 90

mm Hg, respectively. Blood pressures are the on-treatment average of all post baseline

recordings. The quadratic terms for both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were

statistically significant in all age groups (all P <.001, except for diastolic blood pressure in

60–70-year-olds for whom P = 0.006). The adjustment was based upon sex, race, and history of

myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, stroke/transient

ischemic attack, renal insufficiency, and smoking.

Keeping systolic blood pressure below 130 mm Hg is hazardous, especially in those with coronary artery disease. The safe range appears to be the same as what reported by Luchi, 130-150 mm Hg.

We should all keep in mind that untreated systolic hypertension is still a silent killer in geriatric patients but over-controlled is harmful, however and should be avoided.

Pham H. Liem, QYHD20