.jpg)

It dawned on me in the weeks following Tet 1968 that the Theater of the Absurd had ceased to be a laughing matter, even for observers with a sardonic sense of humor. Of course Eberhard Budelwitz, my infallible absurdity barometer, had grasped this much earlier. In his last bizarre commentary before being recalled to Germany for detoxification and subsequent assignment to another Asian capital he articulated this realization not verbally this time as he had in the past; he did not ask nutty questions at the Five O’Clock Follies, for instance questions about submarines for Buddhist monks as a possible defense against leathernecks urinating outside the monks’ pagoda. No, he made his point in a desperate act of inebriated lunacy.

This happened in the Continental while the Time-Life bureau gave a roaring farewell party for correspondent James Wilde, a red-faced and short-tempered Irish-American who had entered the hall of fame of aphorisms about the Vietnam War with a blood-curdling remark: “The stench of death massaged my skin; it took years to wash away.”

Jim was being transferred to Canada, and we were teasing him with questions about his new assignment. “How are you going to keep your blood pressure up on those dry Sundays in Ottawa?” someone asked him. Then, out of the blue, he was gone. After a few more drinks we began to worry about him and organized a search party, which logically began with Jim’s room. His door was ajar. Peering inside, we saw a combat zone. His closet was open and his clothes were strewn all over the place. One of the large French windows had been yanked out of its frame and smashed on the floor. There were bloody footmarks throughout, leading right up to the window.

James Wilde was in his bed, shaking, with his sheet pulled over his head.

“Go away, go away!” he cried.

“Jim, it’s us, your friends! What happened?” we said.

“Oh it’s you? Thank God!” he said, “I just went to my bathroom to relieve myself, then stretched out on my bed for a little rest, and fell asleep. The door opened and in came this naked Kraut scaring the s..t out of me…”

“What naked Kraut, Jim?” I asked, “I am right here, and I am dressed.”

“No, you idiot, not you! I am talking about that other Kraut who always asks boozy questions about submarines for Buddhist monks and things at the Follies. Anyway, he went straight for my closet, took out all my clothes, put on a jacket, went to the window, ripped it out, smashed it on the ground, trampled dementedly on the broken glass, and then jumped head first out of the window. It was frightening, guys, really frightening!”

“Where is he now?” asked William Touhy of the Los Angeles Times.

“I don’t know, probably dead on the sidewalk. I heard a thump.”

We looked out of the window and down on a generous canopy providing additional shade for the patrons the Continental’s terrace below. On this canopy lay our colleague Eberhard Budelwitz, fast asleep, dressed only in Jim Wilde’s jacket. His hands and feet were covered with blood, but otherwise he was intact. We hauled him inside, put some of Jim’s underwear on Budelwitz, and then carried him to his own room, without waking him up. This was the last time I saw Budelwitz. I continue holding him in high esteem for his incisive though seemingly bizarre questions, and particularly for this last performance in Saigon, which in the final analysis did not strike us as bizarre after all. His urge to throw himself out of the window as an exclamation mark behind his reporting career in Vietnam resonated well with some of his peers.

Not that any of us really had suicide on our minds; I certainly didn’t, and I don’t believe Budelwitz did either. Even in his inebriated state, he possessed sufficient wisdom to realize that a hop out of a window and onto a canopy wouldn’t be lethal. But in his whacky way he made a powerful point: What we had just experienced at Tet was the Theater of the Absurd taken to its most ludicrous level. This incident convinced me that the Latin axiom, in vino veritas (in wine is truth), also applied to Screwdriver cocktails, at least in Budelwitz’ case.

Six weeks at home in Hong Kong after my Tet ordeal did little to satisfy my longing for a return to sanity. Two parallel political developments made some Hong Kong-based correspondents wonder about who was really unhinged: was it us, or was it the world we were supposed to cover? Next door, in Communist China, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was reaching its peak. We received reports of the Pearl River being clogged with the corpses of Communist cadres clubbed to death by young Revolutionary Guards. Some were sighted in Hong Kong waters, with their arms tied with wire behind their backs but carrying Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book in their pockets.

Still, from a geopolitical perspective, the news about the Soviet-Chinese split and Beijing’s refusal to have Soviet arms supplies to North Vietnam being transported by rail across Chinese territory was even more dramatic. This should have been received as good news in the United States but it was barely noted in the American media. An even more sensational piece of information followed.

Gillian and I attended a small dinner party at the home of the station chief of a Western European intelligence service. The guest of honor was an American naval captain who mastered six Chinese dialects and held a Ph.D. in Sinology. We knew that he was the U.S. military intelligence officer in charge of analyzing provincial broadcasts and internal communications in the People’s Republic. His place of work, the massive American eavesdropping station, was only a few minutes’ walk away from my apartment.

“Tell me, gentlemen,” he suddenly asked the two journalists present, “Do you also find it sometimes as difficult as I to get the attention of your top editors when you have some hot news?”

“Do I ever!” I replied.

“I don’t,” said my American colleague, “But why are you asking?”

“Well, you see, hardly anything I send back to Washington reaches the President in any consequential form, regardless of how important my news might be.”

“For example?” I asked.

“For example, I had told my superiors of mounting evidence that an armed conflict was likely between the Chinese and the Russians. Some guy at the Pentagon watered it down before it reached the chief of military intelligence. He watered it further down before Defense Secretary McNamara got it. McNamara again watered it down before sending it on to the White House.”

“So what did Lyndon Johnson get to read?” asked my American colleague.

“A meaningless one-liner saying that according to Hong Kong Station, the Russians and Chinese aren’t getting on -- or something banal like that.”

“Why are you telling us this?” I wanted to know.

“Because I believe that the President of the United States should be prepared for military clashes between these two Communist world powers. He will if reads that story in the press. Go and write about it, but please do so on background: not for attribution.”

That night we filed our pieces, and the following morning the world, including presumably LBJ, knew how serious the Sino-Soviet conflict really was. This dangerous situation took a while to reach its climax, but one year after our dinner conversation, Chinese and Russian forces did clash at the Ussuri River.

Driving home from the spooks’ party, I regaled Gillian with the tale of Eberhard Budelwitz’s auto-defenestration as the ultimate performance of the Theater of the Absurd. She laughed.

“I get your point,” she said, “What we have just heard was yet another act of the Theater of the Absurd.”

“Yes, top-level Theater of the Absurd.”

“Frightening,” she said, “It’s enough to want to throw oneself out of the window.”

“Only figuratively speaking, please!”

Then, on February 27, 1968, big news broke: CBS Evening News anchorman Walter Cronkite, home from a flying visit to Vietnam after the Tet Offensive, pronounced sonorously before an audience of some 20 million viewers the Vietnam War unwinnable. This flew in the face of everything many combat correspondents, including Peter Braestrup and I, had lived through at Tet. We knew then what historians are saying now: the Americans, South Vietnamese, and their allies had defeated the Communists militarily.

But Walter Conkrite’s opinion trumped reality, turning a military victory into a political defeat.

“I have lost Cronkite, I have lost Middle America,” said Lyndon B. Johnson, and announced one month later a partial halt of bombing over North Vietnam along with his decision not to seek re-election. With that the Theater of the Absurd crested.

It so happened that on the day Johnson made this announcement, on March 31, 1968, Gillian and I traveled together to Saigon. It was her first time in Vietnam. Most war correspondents kept their families in Hong Kong, Singapore or Bangkok, not only for their safety but also for a sound professional reason: a combat reporter must be able to join a battle on an ad hoc basis without first having to discuss this at great length the night before with his wife at the dinner table.

Gillian was never overly convinced of this argument and became even less so after landing in Saigon. On our Cathay Pacific flight I had warned her how unpleasant the South Vietnamese immigrations officer could be. But when she showed her British passport, the man’s face lighted up.

“Ah, Madame Siemon-Netto, soyez la bienvenue à notre pays!” he said, “Je connais votre époux, bien sûr, mais il m’est une honneur de vous rencontrer.“ -- Welcome to our country. Of course I know your spouse but now it’s an honor to meet you.

“What a charming chap,” said Gillian, giving me a strange look.

“I have flown in here umpteen times, and he never bothered to even say hello to me,” I growled. “But wait till you get to the customs guy. He’ll give us a hard time.”

Well, he didn’t give us a hard time; instead he greeted Gillian just as warmly as the immigration officer. He did not even look at our luggage but simply waved us on. Gillian gave me an even funnier look.

“Normally these guys inspect every one of my knickers,” I mumbled. “But wait till we have to fight for wheels to get us to the Continental. Taxis are no longer allowed to drive up to the terminal.”

Just then a young man, who probably was an Air Force lieutenant moonlighting as a chauffeur, offered to drive us to our hotel in his air-conditioned Buick. At this point Gillian stared at me with an expression of deep distrust.

Monsieur Loi, the Continental’s general manager, welcomed us with a huge smile and guided us personally to Suite 214 where 25 red roses awaited Gillian, compliments of the house. These beautiful flowers intensified her suspicion!

“Why have you kept me away from this charming place for so long?” she demanded to know.

That evening at the Royal, Monsieur Ottavi rolled out the red carpet: artichokes, onion soup, foie-gras, and canard à l’orange, accompanied by a bottle of Château Cheval-Blanc, the finest red wine from Saint Émilion. Ottavi’s famous soufflé au Grand-Marnier followed, together with a bottle of Dom Pérignon champagne. Where had he hidden these treasures in all the years past?

On our way back to the Continental, Gillian stated tersely, “So is this where you are taking your mistresses!”

“Look, darling, whatever you might think, there is something important you must hear,” I said when we reached our room, pointing to the large French windows the panes of which I had carefully Scotch-taped during one of my previous stays as a protection against flying glass in case of a Vietcong rocket attack.

“When you hear a thud tonight,” I went on, “you must immediately come with me to the bathroom and stay there until the attack is over. The bathroom is the safest place in this suite because it has no windows and will therefore offer the best protection against flying glass.”

Not dignifying me with an answer, Gillian curled up in my bed, which, as I had explained to her, had probably once been Graham Greene’s.

Two hours later, the Vietcong lobbed a barrage of rockets from handmade bamboo launchers across the Saigon River into the city, killing hundreds of people, including 19 women and children who had sought shelter in a Catholic church. We spent most of the rest of the night sitting in the bathroom. For Gillian, this was lesson 101 about the Vietnam War: for all its charms, Saigon was indeed a dangerous place.

More importantly, this was an unmistakable message from the Communists to the rest of the world, especially to deluded utopians fantasizing that peace was nigh after the American bombing halt and Johnson’s announcement on that very day that he would not seek re-election. One did not have to be member of Mensa International to grasp the significance of this attack: with the help of Walter Cronkite and likeminded communicators, a military victory had been turned into a political defeat for the United States and South Vietnam. A staggering number of Communist soldiers had fallen during the Tet Offensive, but the Vietcong made – from their perspective -- the best possible use of the irrational reaction in the United States to this appalling bloodbath, a reaction confirming Vo Nguyen Giap’s conviction that democracies were not psychologically equipped to fight a protracted war. In the arrogant, defiant and callous manner of totalitarians, the Communists retook the initiative by murdering and terrorizing more civilians.

This time our stay in Saigon was brief because we had been given visas to visit Cambodia, a rare occurrence. Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the Cambodian chief of government, seldom allowed Western journalists into his realm, the easternmost part of which the Vietcong used as a staging and supply area for their war against South Vietnam. Before we boarded our plane to Phnom Penh, though, I paid Wilhelm Kopf, the West German ambassador in Saigon, a courtesy visit.

Unexpectedly, Hasso Rüdt von Collenberg entered, apologizing for interrupting our conversation. The young baron’s face looked even paler than usual. He whispered something sounding like code. Kopf’s chin sagged to his chest. Following intuition, I ventured a guess:

“They have found the bodies of the German doctors in Huế haven’t they?” I said.

Hasso von Collenberg stared at me distraught and answered, “Yes, but it’s not official yet. We must first inform Bonn.”

“I understand. Tell me off the record then: what happened?”

“They found the bodies of Professor and Mrs. Krainick, of Dr. Discher and Dr. Alteköster in a mass grave about 20 miles west of Huế. They were blindfolded and had their arms bound with wire behind their backs. They were made to kneel before being shot through the back of their heads, and then dumped into the ditch.”

As the ambassador and I were listening to him, we could not know that this description would soon apply to von Collenberg’s own fate a few weeks later when the Vietcong murdered him not far from the embassy in a side street of Cholon, Saigon’s Chinatown.

The young diplomat told us that the Rector of Huế University had identified the bodies of his German colleagues, and that their condition allowed one significant preliminary conclusion: they must have been alive at least six weeks after their abduction. Given Hanoi’s efficient command structure, the execution of these four West Germans could therefore not have been a “mistake” committed in the heat of battle; they weren’t “collateral” damage of an act of war. Despite pleas from around the world, Hanoi did not act to save these innocent lives, although it had plenty of time to do so. Thus we must assume that the executions of these, and thousands of other guiltless people had been intentional and accordingly were classed as war crimes either ordered by a government or committed with the regime’s connivance.

One year later, at the Paris peace conference, which ultimately led to America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, I ran into a reporter of Giai Phong, the Vietcong news agency. He told me that he had covered the Tet Offensive in Huế. Comparing notes, we found that at one point we were less than 100 yards apart. I wanted to ask him: “Why did your people massacre thousands of women and children? Why did they murder my West German friends whose only ‘crime’ was to heal Vietnamese, regardless of their political loyalty?” Alas, I didn’t. It seemed useless to ask him these questions; he was not alone. There were always “minders” within earshot, and at any rate, the Vietcong had already given Western journalists at Communist receptions in posh Paris salons their ridiculous version of what had transpired in Huế. They said this was the work of the CIA.

To this day, I am unsure about the origin of this preposterous fib. Was it the brainchild of some boneheaded party apparatchik in Hanoi? Or was it the invention of yet another West German physician, the frenzied psychiatrist Erich Wulff who had played an unsavory role during his tenure in Huế? In 1963 he had agitated against the government of President Ngo Dinh Diem and the United States, and passed medicines and surgical instruments secretly to the Vietcong. Later, after being made to leave the country, he testified before Bertrand Russell’s International Vietnam War Crimes Tribunal. When I met him in Huế in 1965, he accused his neighbor Horst-Günter Krainick of nurturing a racist bias against the Vietnamese people and vented his outrage against Krainick’s wife for swimming in the Cercle Sportif every day and socializing with Americans. Neither I nor any other acquaintance of the Krainicks’ had ever detected anything other than a great love for the people they had come to help.

In 1968, Wulff wrote under the pseudonym, Georg W. Alsheimer, a revolting polemic titled, Vietnamesische Wanderjahre, or Years of Travel in Vietnam (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1968). In this book he claimed that a top CIA official by the name of Bob Kelly had told him about a CIA terror program called Black Tactics. According to Wulff, this program consisted of young men dressed up as Vietcong killing old men, women and children, to stir up hatred against the Communists.

The North Vietnamese and Vietcong explanation of the Huế massacre corresponded to Wullf’s version. In fairness to most Western correspondents, they found this tale unconvincing. In the meantime, Erich Wulff offered yet another harebrained story at leftist gatherings in West Germany: he ventured to suggest that Dr. Discher, Dr. Alteköster and the Krainicks might have been killed by their own students as an act of revenge for bad grades or, alternatively, by jealous Vietnamese colleagues.

Again, I am jumping ahead of my narrative. At this point in my tale I was still in the ambassador’s office in Saigon. The expression of sorrow in Hasso von Collenberg’s face was indescribable. I remember thinking: “What a noble mind! What a decent and brave man! Since the beginning of the Tet Offensive he had driven about Saigon day and night making sure that German citizens were safe. He never went home, but slept on a cot in his office. He had prayed that the Communists would spare his friends in Huế, which was all he could do, and now they were dead. Our government should be so proud of him!” If it was it didn't show it. All that is left of his memory are his photograph and two paragraphs of text in a 2011 German Foreign Office brochure titled, Zum Gedenken (In Memoriam). The West German foreign minister at that time was Willy Brandt, a social democrat who had given détente, or the thaw in the relations with the Soviet bloc, the highest priority in his policy. One can only surmise that he thought it might be detrimental to this objective to fuzz over the murder of one of his envoys.

With dark premonitions, Gillian and I boarded our plane to Phnom Penh, embarking on a journey back in time, or so it seemed. Cambodia’s capital was then still the way Saigon had been in balmier days: very French but also very exotic, quirky, glamorous and peaceful. Lissome, bikini-clad wives and daughters of French military and civilian advisers lined the swimming pool of the hotel Le Royal, but in reality they were just decorative trimmings. In truth only one person mattered in all of Cambodia: Prince Sihanouk who was once its king and would become king again. But at the time of our visit he contented himself with playing a host of different roles: he was the chief of government, chief producer and star of countless films, chief radio and television commentator, chief choreographer of the Royal Ballet, editor an chief of a high-brow magazine, chief saxophonist and composer-in-chief writing orchestral pieces resembling Charlie Chaplin’s romantic tunes. He was also the obedient husband of the magnificent Princess Monique, a stern disciplinarian. She was the daughter of an Italian bricklayer and a wily Vietnamese woman. When Monique was 15 she caught Sihanouk’s eye at a beauty contest. So her mother slipped her through a back door into the royal palace. Monique never slipped out again. Sihanouk, then king, fell in love with her and married her almost instantly. They remained together until his death at the age of 89 in 2012.

Sihanouk’s form of neutralism was amusing. Boulevards named after Mao Zedong, John F. Kennedy and Charles de Gaulle crisscrossed Phnom Penh. It was fun watching Sihanouk handle diplomats from both sides of the East-West divide with equal irreverence. At the opening of a new hotel in Sihanoukville he hopped into a swimming pool the water of which was brown and seemed dirty because the staff had forgotten to replace it with fresh water. “Excellence!” he yelled at the Chinese ambassador standing aloofly at the rim of the pool, “If your Chairman Mao can swim in the cold Yangtze, you can surely join me in a balmy dip.” Immediately, the ambassador shed his Mao jacket and jumped, while Sihanouk, laughing, focused on the Soviet ambassador, saying in his high-pitched voice, “And you, Sir, should tell your government to tear down the Berlin Wall!” Not until two decades later, an American president, Ronald Reagan, said the same words to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

With my colleague Ronald Ross of the Minneapolis Tribune and his wife Marilyn, Gillian and I hired a chauffeur-driven Peugeot station wagon to take us to the temples of Angkor. Throughout this journey through an enchanting and unthreatening countryside we wondered how much longer Cambodia would be spared the grim fate of neighboring Vietnam. Sihanouk had dark forebodings. He had warned us: “The Khmers Rouges want to kill all my little Buddhas,” meaning his people. The Khmers Rouges numbered only about 300 men then. Their leader was a former schoolteacher named Saloth Sar, alias Pol Pot, who during his student years in Paris had been part of Jean Paul Sartre’s entourage. Seven years after our visit to Cambodia, Pol Pot joined the ranks of 20th century’s worst genocidal fiends, alongside Hitler, Stalin and Mao Zedong by killing one third of his fellow countrymen -- almost two million people.

After our return to Phnom Penh, Sihanouk invited a group of visiting foreign correspondents on an excursion to the Parrot’s Beak area by the South Vietnamese border. The stated objective of this trip was to show us evidence of armed incursions by ARVN and U.S. forces into neutral Cambodia’s territory, but he also had an ulterior motive. The Parrots Beak was known to be a North Vietnamese and Vietcong base and rest area, and also constituted the terminus point of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Driving east, some of us found evidence of a violation of Cambodia’s neutrality by Hanoi more compelling: On car ferries crossing estuaries of the Mekong River our Peugeot was wedged in between Land Rovers filled with military types whose signature footwear gave them away as Vietnamese Communists. They wore sandals made from worn rubber tires: Ho Chi Minh Sandals they were called.

We knew then that happy Cambodia was merely a paradise on parole. We enjoyed its humor, beauty, sensuality, good food and its idiosyncratic ruler whom cliché-mongers in the Anglo-Saxon media loved to label mercurial. Nobody enjoyed all this more than a cheerful young freelance journalist named Sean Flynn. He was Errol Flynn’s son. Two years later, he became one of the first Westerners for whom paradise in parole turned into hell. The Khmers Rouges captured him, held and probably tortured him for about twelve months, and then killed him.

Following our trip to the Parrot’s Beak, Gillian and I returned to the Royal, where a telegram was awaiting us: Egon Vacek, the foreign editor of Stern magazine, invited us to join him at the Siam Intercontinental in Bangkok, and there I made the biggest blunder of my career. Vacek offered me a very generous salary and the glamorous position of Stern’s North American correspondent based in New York and Washington. I accepted, which meant leaving the Axel Springer Corporation after my contract expired in the fall of the following year.

Today I realize that this was my own ludicrous act in the Theater of the Absurd. Springer had been a wonderful employer, and the company tried to persuade me to stay. Herbert Kremp, the erudite editor-in-chief of Die Welt, Springer’s flagship newspaper, offered me even the prestigious post of Tokyo correspondent, which would have allowed me to return to Indochina frequently. I dared not accept this challenging assignment without a thorough knowledge of Japanese.

Stern seemed attractive at the time because, as a magazine, it offered me a better opportunity than daily newspapers to write big and colorful feature stories. I also liked Egon Vacek, my future boss, a seasoned former foreign correspondent and a political moderate at a time when Stern drifted further and further to the left. When he died of cancer a few years later, I was left without allies within the increasingly leftwing power structure of the biggest weekly magazine in Western Europe. No more need be said here about this mistake, which resulted in the most unpleasant episode of my professional life.

But my love affair with Vietnam did not end there and then. As I was fulfilling the last year of my Springer contract, my sense of dark presentiment intensified. When I returned to Saigon from my trip to Cambodia and Thailand, my friend Lanh, the German-speaking ex-trombonist of the French Foreign Legion, came to see me at the Continental.

“I am learning Russian now,” Lanh announced.

“Why not Chinese?” I asked him.

“Because the Russians will be here before long, not the Chinese. You’ll see! A Russian will be inhabiting your suite, or perhaps an East German!”

“God forbid!”

“Yes,” said Lanh, “God forbid!”

Seven years on, after the Communist victory, Russians and other East Europeans would indeed be billeted in the Continental, but by that time Lanh had fled to Paris.

One emblematic scene of my last elegiac months as Springer’s Vietnam correspondent remained deeply ingrained in my mind: I traveled with Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky on an Air France Boeing 707 from Paris to Saigon. Ky had led the South Vietnamese delegation at the Paris peace talks where his wife, Tuyet Mai, charmed everybody with her beauty and the elegance of her borrowed mink. But on the journey back all this glamour seemed to have faded. I sensed that Ky had lost his normal exuberance. We talked for many hours about many things, but most of what he said sounded like vain attempts to reassure himself; he knew that the Americans were determined to leave Vietnam. The only real questions to be resolved at the peace talks were: how and when?

As we spoke, he kept looking at the door to the cockpit.

“Why are you staring at the cockpit all the time?” I asked him.

“Because all I am really longing for is being a pilot again,” he answered softly, and I detected a trace of despair in his voice. “Go chat with Tuyet Mai a little,” he said abruptly, turned on his side and closed his eyes. As it transpired, he would never become a pilot again. The lowly job of a liquor store manager in Huntington Beach, California, was all fate held in store for him.

This snapshot of our Air France flight to Saigon told me more about the real story behind the Paris peace talks than anything I had heard in several weeks of covering them. It seemed symbolic for the fate of all of South Vietnam.

I took up my new position as Stern’s North American correspondent on September 1, 1969. The very next day Ho Chi Minh died. His obituary was my first Stern article, and writing it directed my mind straight back to the horrors of Hue because I had to describe the significance of the Lycée Quoc Hoc he had attended as a young boy. This revived my memory of the thousands of starving and freezing people I had encountered on the grounds of that school, all driven from their homes by Ho’s Tet Offensive. In the obituary, I also made a point of describing Ho as “the man from the land of the wooden spoon” because he hailed from the Central Vietnamese province of Nghe Anh, the people of which were so poor and stingy, that when they traveled they carried with them wooden spoons, which they would dip into the complimentary nuoc mam, or rancid fish sauce, to add protein to the only dish they could afford to order in restaurants: a bowl of rice.

My long farewell to Vietnam continued throughout my three and a half North American years with Stern. Even if I had wanted to, it was impossible to take a leave of absence from Vietnam. Not a day went by when it didn’t dominate the news. There were the interminable peace marches, there was the killing of four demonstrators at Kent State University in Ohio, and there was the murder trial of Lt. William Calley, which I covered in Fort Benning, Georgia. As a platoon leader, Calley had played a pivotal role in the massacre by American soldiers of between 347 and 504 civilians in the South Vietnamese village of My Lai. Attending Calley’s court-martial I couldn’t help recalling the refusal of an American television cameraman to film a mass grave in Huế, saying, “I am not here to spread anti-Communist propaganda.”

Of course I was gratified when Calley received a life sentence and was outraged that he was the only U.S. officer tried for this war crime. I was beside myself when President Richard M. Nixon ordered his release. But the fact that his crime overshadowed the genocidal behavior of the Communists in the public mind troubled me because the difference between these two events had got lost in the hysterical rhetoric that has become the most unbearable feature of a media-driven culture: Calley’s crime violated stated U.S. government policy and internationally accepted standards of warfare. The North Vietnamese and Vietcong atrocities, on the other hand, were committed as an integral part of a government policy that included a military strategy based on terror. To my mind it constituted massive malpractice by the media that they have not made this crucial point unmistakably clear to the general public.

In the spring of 1972 I returned to Vietnam for the last time. More than anything I wanted to see Huế again, the city where seven years earlier I had spent an enchanting night on a sampan listening to the songs of a beautiful girl with long black hair. I remembered her hauntingly sensuous voice and the exotic tunes of the trapeze-shaped Đàn Đáy, a three-stringed instrument she strummed as we floated down the River of Perfumes. In an almost perverse way, I pined for this martyred city I had left in an armored landing craft after spending frightening hours in house-to-house combat during the Tet Offensive. I kept recalling the three sets of fatigues I wore, one on top of the other, all reeking of dirt and death. I also felt a morbid and yet melancholy urge to retrace my stops along Le Loi Boulevard, and take one last look at the ugly Cité Universitaire, where the murdered German doctors had lived.

This time I traveled in the company of Stern photographer Perry Kretz, a tough German-American who was wholly bilingual in a unique way: he spoke a New York-accented English and Kölsch, the hilarious dialect of Cologne. It was very good to have him as a companion because he had seen battle many times before, starting in the Korean War where he had seen combat as a soldier in the U.S. Army. Perry could be relied upon not to panic.

We knew that a tough assignment lay ahead of us. The Communists had just launched their Easter Offensive, their largest campaign so far. Its aim was not so much to conquer territory, as to gain bargaining chips for the Paris peace talks. An enormous invasion force poured into South Vietnam from Cambodia, Laos, and especially in a most brazen manner across the so-called Demilitarized Zone separating the North and the South; part of this force was, as I found out later, 25,000 elite soldiers just back from training in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries, including East Germany.

The North Vietnamese had already taken Quang Tri, where in 1965 during my memorable visit with the International Control Commission, I had been the interpreter for a Polish major when he needed treatment for a head wound from a volleyball accident. But the Communist advance toward Huế was stopped, not by the Americans, who by that time had withdrawn all but 69,000 men from Vietnam, but by the best of ARVN: the Airborne, the Vietnamese Marines, the First Division and the Rangers, all superbly led and defying the fabrication spread by some U.S. reporters that ARVN could not fight.

In truth, they proved more disciplined and professional than their northern adversaries. “The North Vietnamese brought 100 Soviet-built tanks across the DMZ but then didn’t know how to handle them,” an American advisor told us on the flight from Saigon to Huế, “They had to abandon scores of these tanks. Drive up Highway One, and you’ll find part of the road lined with abandoned Soviet armor.”

Perry and I engaged a driver with the looks and demeanor of an archetypal upper class Huế intellectual. He was a reserved and earnest young man, near-sighted with thick eyeglasses and a fine command of French. His name was Hien. He owned a Jeep in good condition and equipped with sandbags as a protection against shrapnel in case we hit a landmine.

First we drove up to the citadel, which I had not been able to visit at Tet 1968 because it was under Communist control. However, at this time we found battle-weary South Vietnamese soldiers resting in hammocks strung between cannons dating back to the early 19th century. These guns were symbols of hope and pride for them, especially at a time when their elite units – and not the Americans, who were about to depart – had stemmed a new massive invasion by Communist forces. The cannons reminded them that their country had been divided before for 200 years. It was a South Vietnamese prince, Nguyen Anh, who ended this division by defeating the northern Tay Son Dynasty in 1801/1802 with the help of 300 French mercenaries.

Nguyen Anh then proclaimed himself emperor, assuming the title, Gia Long. He seized bronze pieces of armory from the beaten Tay Son forces and ordered them melted down and recast as nine big guns, naming five of them after the five elements metal, wood, water, fire and earth, and the other four after the four seasons spring, summer, autumn and winter. They had never fired a shot in anger but were only used for ceremonial purposes.

“This historical detail is very much on our mind,” said Brigadier-General Bui The Lan, the commander of the South Vietnamese Marines who had established his headquarters in the Citadel. I had known Gen. Lan for years. In the eyes of many U.S. officers, foreign military attachés and reporters in Saigon this wiry Hanoi-born soldier ranked among the toughest and most capable commanders in this conflict.

“If Huế falls, the game is over for us,” Lan continued. “This is why our government has deployed our best units north and west of here. If Vietnam is ever reunified, then Huế must become its capital again. The North Vietnamese know it too, which is what their current offensive is all about.” On the following day a North Vietnamese prisoner of war confirmed this to me.

“What was the object of this operation, according to your officers?” I asked him.

“To take Huế and establish a revolutionary government in the Forbidden City immediately,” he replied.

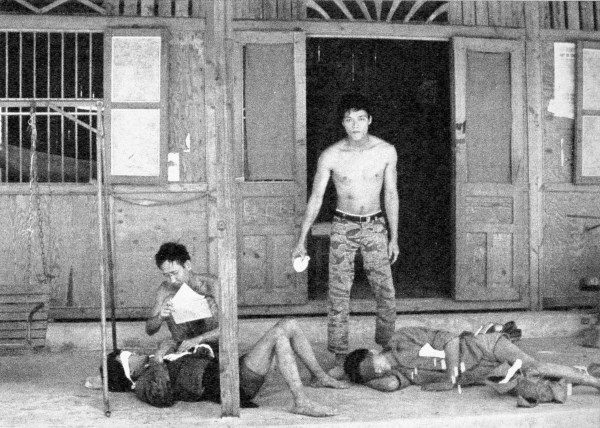

We interviewed him at a forward position some 20 miles north of Huế. He was squatting on he ground, handcuffed and blindfolded while a South Vietnamese captain was fanning the flies from his face, a sergeant slipped a lighted cigarette between his lips, and a corporal gave him water. Perry and I were very moved by these gestures of compassion toward an enemy fighter at a time when the South Vietnamese were fighting for their country’s survival.

.jpg)

Perry Kretz

ARVN soldiers relaxing on early 19th century canons

in the citadel of Huế

Perry Kretz

Perry Kretz, General Lan of the Vietnamese Marines

and the author in Huế

Perry Kretz

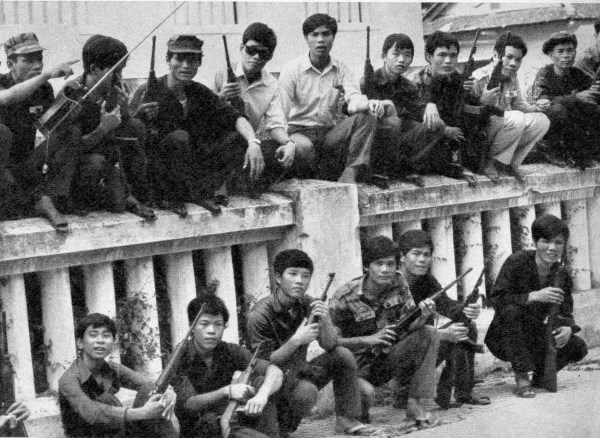

No love for the Vietcong: Huế teenagers volunteered

to fight the Communists

Perry Kretz

South Vietnamese soldiers tending to wounded

North Vietnamese POWs

The soldier was only 17. He hailed from Nam Dinh, a city 50 miles just South of Hanoi. After three months’ basic training he was sent with the 66th North Vietnamese regiment to Quang Tri where his first battle turned out to be his last. “Three quarters of the men in my battalion died, and I was wounded in the head,” he told me, “then I was captured.”

We drove north on Highway One, which the French called “La Rue Sans Joie,” or Street Without Joy, because so many soldiers and civilians had died there during the first Indochina War. We knew that we would not get far because the forward-most North Vietnamese units were reported to be very close. The object of this trip was to put the state of this route in a historical context, comparing it with what I had read in Bernard Fall’s books; I also wondered if the buffalo boys I had written about so much previously were still there; as it turned out, they were not, and this was an ominous sign. Route One had become an eerie thoroughfare. Ours was the only vehicle on this road that was the dividing line between North Vietnamese positions to the west, and the South Vietnamese units to the east. Mortar and howitzer rounds were flying overhead in irregular spasms.

Perry sat in the passenger seat next to Hien, and I was in the back staring with increasing alarm over Hien’s shoulder at the speedometer. Its needle rarely passed beyond the 30-kilometer mark. His nose pressed against the inside of his windshield, near-sighted Hien dawdled dangerously along this perilous stretch of road.

“Drive faster, Hien,” I begged him, “We are getting sniper fire. Only speed can save us.”

“I must check the surface of the road for mines, Monsieur,” said Hien, “But my eyes aren’t good enough to spot them.”

“Then let me drive, my eyes are fine,” I said.

“No, Monsieur, I can’t do that. This car is only insured in my name,” he answered disingenuously and Perry went apoplectic.

“Ya hoid him, ya schmuck, drive faster!” Perry howled in a tone that might have commanded respect in New York, but was definitely not the ideal way to persuade a Huế intellectual.

Hien threw a fit. He slammed on the breaks. The Jeep came to a halt at the worst place one wants to be stuck in the middle of a war: at an unprotected spot on an open highway, exposed to all sides, with artillery rounds from both sides whooshing overhead.

Louder and louder Hien and Perry argued in four languages: Hien with a high-pitched voice in a mixture of Vietnamese and French, and Perry shouting partly like a New Yorker, partly like the native of the Rhineland he was. The Theater of the Absurd reached a level where death had become a distinct probability. I grabbed Hien’s car key and said, “I want to survive this and am running for cover. If you calm down before you are dead, join me in the ditch.” Then I jumped out of the back of the Jeep and ran, ducking, some 500 yards until I found a cavity by the side of the road deep enough to serve as a foxhole.

Hien and Perry continued to argue, but not for long. They joined me in my foxhole until the battle had simmered down. Miraculously, Hien’s Jeep survived unharmed.

“I’ll drive,” I said, turning the jeep around. I hit the accelerator and zigzagged back in the direction of Huế, trying to avoid snipers and at the same time weave my way around patches in the surface of the road that seemed to suggest the presence of mines.

As we drew nearer to the city, we came across only one other civilian vehicle. It was a three-wheeler Lambretta bus, or Lam, the driver of which seemed unperturbed by sniper fire and mortar shrapnel. Suddenly he stopped, and so did we, intrigued by the Lam’s cargo and passenger. We saw two tiny coffins and a woman with black-lacquered teeth. She threw herself and screamed, “O my children, my children, why did you left me behind?”

“What happened?” I asked the Lam driver. Hien translated.

“They died last night in a North Vietnamese artillery attack that completely destroyed our village over there,” answered the driver, pointing at a cluster of ruined huts a few hundred yards south along Highway One. Eight South Vietnamese soldiers emerged from foxholes near the road and grabbed the two coffins. They buried them at the edge of a field, cautioning the wailing mother not to get too close.

“Mines!” they warned.

From a short distance, the woman threw a fistful of candy into the grave before the soldiers closed it.

We continued our journey. At the outskirts of Huế we came across dozens of armed teenagers squatting on a wall. They looked too young to be soldiers.

“Who are they?” I asked Hien.

“Militia boys,” he said. “They have all volunteered to fight the Communists.”

“This seems new,” I ventured, “especially here in Huế where people tended to stay aloof from the war.”

“No more,” Hien explained. “We used to hate foreigners, first the French, then the Americans. But after Tet we just hate the Communists – all of us: from schoolboys all the way up to the Dowager Empress.”

“What? There is still an empress around?”

“Of course. She is Emperor Bao Dai’s mother. Her name is Hoang thi Cuc,” he answered, “We address her as Đức Từ Cung, which translates into most virtuous kind lady.”

“Đức,” I said. “That’s my nickname and it also means German. So we have something in common.”

For once the earnest Hien permitted himself a smile and a little jest:

“Except that she is a Đức Sang-Bleu” -- a virtuous blueblood.

“So she has not joined her son in his exile in the South of France?”

“No, she lives right here in a villa off Le Loi Boulevard.”

“Do you know her, can you arrange an interview?” I asked.

“Yes, I know her well. But, no, she won’t give you an interview. Empresses don’t give press interviews, just audiences. I think I can arrange this for you, though.”

Two days later, Hien drove us to the empress’s residence. The first thing I noticed was a graffito on her garden wall. “Cat dao,” it said: cut the head off. But the next word, my, meaning American, was whitewashed over, clearly a political statement.

A very thin courtier wearing a well-worn tunic instructed us how to behave in the presence of Her Majesty. We were to greet her with our hands folded before our face. We were not to touch her and not to speak first. It was her privilege to open a conversation.

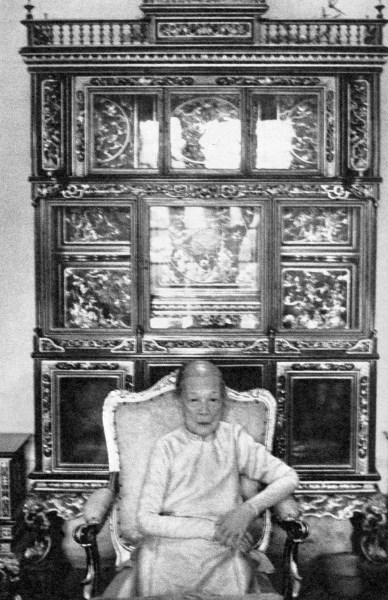

We were led into her living room, and there, in an elaborate arm chair in front of an even more elaborate family altar bearing photographs of her late husband, Emperor Khai Dinh, and her far-away son Bao Dai, sat Đức Từ Cung, a tiny 83-year old lady dressed in the gold-colored Ao Dai reserved only for monarchs. She chain-smoked Bastos cigarettes made from strong black tobacco.

Jasmin tea was served in gold-rimmed porcelain cups. Đức Từ Cung spoke softly in Vietnamese, with her courtier translating. She made it clear that she saw herself as the placeholder for her son, the rightful ruler of Vietnam. She would never voluntarily leave Hue unless the Communists came for good. But she hadn’t left during their three-week reign of terror at Tet 1968.

“One cannot desert one’s people,” she insisted. “The people of Huế are still monarchists. They come to see me all day long – the rich and the poor, noble and commoner, high and low. President Thieu and Vice President Ky recently sent their wives to me to pay their respects, and Col. Thon That Khiem, the governor of Thua Thien Province consults me all the time.”

Listening to her was a melancholy experience, much like meeting Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia in 1968. Was this yet another episode of the Theater of the Absurd? I didn’t think so. Compared with what I had lived through in Huế, it struck me as a glimpse of what normal cultured life in this country should have been like, and it saddened me when I heard that, in order to finance the monarchist movement, she sold off porcelain vases from the imperial family’s ancestral temples.

Perry Kretz

Receiving at an audience:

Dowager Empress Đức Từ Cung

There was one more thing to do before leaving Huế for good: As a railroad buff I wanted to pay its old train station a final visit. Of course rail travel in Vietnam had long been interrupted, but I was always moved by the way in which the Vietnamese maintained at least the appearance of its continuity, meticulously refreshing timetables and fare schedules.

“Let’s be there at eight o’clock in the morning,” Hien suggested.

We arrived a little earlier. Walking the platform, we noticed a faded sign informing us that Saigon was 1,041 kilometers away and Hanoi 688 kilometers. A diesel locomotive stood there, engine running. Together with one luggage car it made up the Trans Indochina Express that was once legendary.

The stationmaster appeared, unrolled a red flag, waved it, and blew a whistle. The locomotive tooted, and at eight o’clock sharp the train left the station. Five minutes later it was back, having traveled no more than one kilometer, roundtrip. The engineer, a man in his fifties named Duong, turned off the engine. The stationmaster rolled up his red flag, and thus their workday ended. Once again they had proven that the Trans Indochina Express was still around.

Strangely, this scene did not seem absurd to me, but instead virtuous, or đức in Vietnamese, for it attested to hope in the face of calamity. As we left the station, 20 cyclopousse drivers were waiting outside with their pedicabs lined up in perfect order.

“Why are you here?” Perry Kretz asked the lead rickshaw coolie.

“Where else should we be?” he replied.

There and then I understood that there was logic to the Theater of the Absurd.

Perry Kretz

At a station without trains in Huế, pedicab drivers

wait for phantom passengers